How I Build Automated Web Scraping Pipelines in Google Cloud

We live in a world increasingly driven by data to make smarter, faster, and more informed decisions. The data behind these decisions can be scattered all across the internet, making it, at times, a challenge to manually compile and analyze. I’ve been using website scraping over the past couple years to scrape sport statistics to get a deeper insight into games and the players in them. This has allowed me to carefully select the data I need from multiple sources and compile it in a single destination that is easily readable and formatted in a way that best suits my needs.

In this article, I’ll walk through a typical, slightly watered down, end to end process I use to building an automated data scraping pipeline. I’ll be using the infamous Books to Scrape website as the target for this article.

If you are interested, all the Python and Terraform code used here is available in one of my GitHub repositories here.

Technologies Used

A majority of my cloud-based projects reside within my Google Cloud Platform (GCP) organization and my data scraping pipelines are no exception. To provide an idea of the typical components that make up a pipeline and to get an idea of what to expect to see throughout this article, I’ve listed them below along with their purposes.

Python (and the Scrapy Framework) - Python is a great tool for scraping and working with data. There are countless libraries and frameworks already built and well established that make scraping data and working with it easy. I specifically use a framework called Scrapy for its simple interface and its crawling abilities which I talk about later.

Artifact Registry - Cloud Run runs applications as container images. Artifact Registry provides the landing zone for my Scrapy container images.

Cloud Run - A fully managed compute platform that runs my scraping jobs as a container.

Cloud Scheduler - Used to automatically run the Cloud Run scraping job at specified times. If you’re not familiar with it, think of it as a managed cron job.

Google Sheets - Once the data is scraped, it needs to be stored somewhere for further interaction. This components is the most fluid and is chosen based on use case. For this article, I’m showing Google Sheets but this could be easily swapped out for BigQuery, AlloyDB, CloudSQL, etc.

I’ve structured this article in such a way that each components has its own sub-section so if you are interested in reading about a specific component, you can easily do so.

Architecture

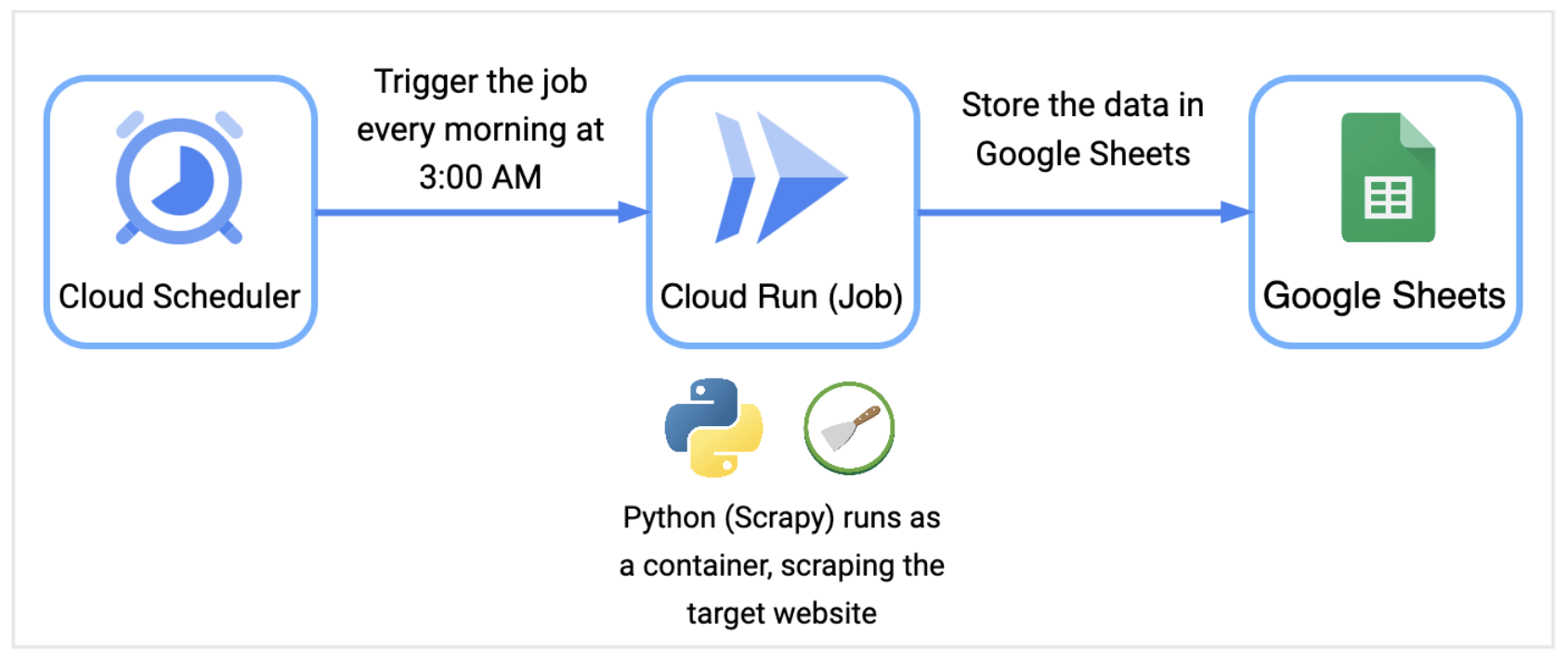

Before diving further into each component of the pipeline, I wanted to provide an architecture diagram to show how the core components tie together.

The Cloud Scheduler triggers the Cloud Run job every morning at 3:00AM which executes the Python application to scrape the data from the target website, in this case is Books to Scrape. As the data is scraped, Scrapy will store the data in Google Sheets.

Google Sheets

For this article, I chose Google Sheets as the data landing zone primarily for its simplicity and because it doesn’t incur additional costs compared to some other destinations.

I’m assuming that if you’re reading this, you know how to create a new Google Sheet. If you’re following along, I’ve set up my sheet as follows:

| A | B | C |

--|-------|-------|--------|

1 | Title | Price | Rating |

--|-------|-------|--------|

Later in the article, I mention sharing the Sheet with a dedicated GCP Service Account, giving it

Editorpermissions so that it can write the data to the Sheet after its scraped.

Python and Scrapy

In all of my data scraping pipelines to date, I have consistently relied on Python and Scrapy. Python’s extensive libraries make it an ideal choice not only for scraping the websites I need but also for analyzing the data I collect. Scrapy, a framework specifically designed for web scraping, simplifies the process by handling tasks like crawling through multiple pages, cleaning data, and storing it, all within a single library. For me, this makes it the go-to tool for this type of work.

For each pipeline, I create a new Scrapy project using their built-in startproject command.

scrapy startproject bookstoscrape

I typically start with defining my Scrapy Items. Items provide a way to structure our scraped data. For this particular pipeline, we are scraping books, so I defined a single Book Item as shown below:

# bookstoscrape/bookstoscrape/items.py

import scrapy

class Book(scrapy.Item):

title = scrapy.Field()

price = scrapy.Field()

rating = scrapy.Field()

With the book Item defined, I’ll move onto building the Scrapy Spider. The Spider is a class that allows me to define how a site, or multiple sites, are scraped and how that data is extracted.

In this example, I created a new Spider called BooksSpider and provided it a name, the allowed domain it should scrape, and a starting URL. I then defined a parse function which defines the logic to extract the title, price, and rating of each book listed on the page using CSS selectors. The data is stored in a Book item, which is yielded for further processing or storage.

# bookstoscrape/bookstoscrape/spiders/books_spider.py

import scrapy

from bookstoscrape.items import Book

class BooksSpider(scrapy.Spider):

name = "books_spider"

allowed_domains = ["books.toscrape.com"]

start_urls = ["https://books.toscrape.com/"]

def parse(self, response):

books = response.css('article.product_pod')

for book in books:

book_item = Book()

book_item['title'] = book.css('h3 a::text').get()

book_item['price'] = book.css('.product_price .price_color::text').get()

book_item['rating'] = book.css('.star-rating::attr(class)').get().split()[1]

yield book_item

To complete a scraper, you need to define what to do with the scraped data. As I mentioned earlier, I’ll be using Google Sheets as the landing zone here. Scrapy uses the concept of an Item Pipeline to process the data scraped data. This is where I’ll define the logic to authenticate to Google Sheets and store the data.

# bookstoscrape/bookstoscrape/pipelines.py

from itemadapter import ItemAdapter

import os

import sys

import gspread

import google.auth

class GoogleSheetsPipeline:

def __init__(self):

try:

spreadsheet_name = os.environ['SPREADSHEET_NAME']

worksheet_name = os.environ['WORKSHEET_NAME']

except KeyError as e:

sys.exit(f"Required environment variable {e} not set.")

credentials, project_id = google.auth.default(

scopes=[

'https://spreadsheets.google.com/feeds',

'https://www.googleapis.com/auth/drive'

]

)

gc = gspread.authorize(credentials)

spreadsheet = gc.open(spreadsheet_name)

self.worksheet = spreadsheet.worksheet(worksheet_name)

def process_item(self, item, spider):

adapter = ItemAdapter(item)

body = [item["title"],

item["price"],

item["rating"]]

self.worksheet.append_row(body, table_range="A1:C1")

To break down this code, it defines a Scrapy pipeline (GoogleSheetsPipeline) that appends scraped book data (title, price, and rating) to a specified Google Sheets worksheet. In the initialization function it determines both the spreedsheet and worksheet name by reading in environment variables, authenticates with Google APIs using Application Default Credentials (ADC), and connects to the specified worksheet. In the process_item method, it converts the scraped item to a list of values and appends them as a new row to the sheet.

With the code done, I need to now need to build a container image for this application so that it can be run in Cloud Run. For this article, I’ve kept the Dockerfile simple (ie. no multi-stage build).

# Dockerfile

ARG PYTHON_VERSION=3.12

FROM python:${PYTHON_VERSION}-slim

RUN apt-get update && pip install --upgrade pip \

&& pip install --disable-pip-version-check --no-cache-dir gspread scrapy

COPY . /app

WORKDIR /app/bookstoscrape

USER nobody

ENTRYPOINT ["scrapy", "crawl", "books_spider"]

With that done, the final task is to build and push this image to a remote container registry. When creating new pipelines, I’ll use a combination of Cloud Build and Artifact Registry to build and store the container image. The Cloud Build configuration YAML can be found here in the Git repository. I can trigger a build and push with the following gcloud command:

gcloud builds submit \

--region=$REGION \

--config=cloudbuild.yaml \

--project=$PROJECT_ID

Cloud Run Jobs

To deploy my scraping pipelines, I’ll configure the Cloud Run jobs to use the container images I built and stored in Artifact Registry, specifying any required runtime environment variables such as target URLs, Google Sheets configuration, and other necessary parameters. This setup allows me to have my pipeline run on fully managed infrastructure - meaning I don’t need to manage any compute - and ensures I only incur cost during execution. This makes it an ideal solution for both ad-hoc and scheduled data scraping tasks.

An important point to note here is authentication to Google Sheets. In my pipelines, I’ll create a dedicated GCP Service Account for the Cloud Run job to run as and ensure that the service account has the necessary permissions to edit my Google sheet. To do this, once you create the service account, retrieve its email and add it as an Editor to your Google sheet.

An example of the Terraform code I typically use to create the required service accounts and deploy a Cloud Run Job can be found here.

Cloud Scheduler

An important component of my scraping pipelines is that they run automatically, at a specific time. For example, the piplines that I mentioned earlier responsible for scraping game data need to run every day after all the games are completed. To do this, I leverage Cloud Scheduler to trigger a Cloud Run job to run every morning at 3:00AM EST. This allows me to have all my data scraped and stored by the time I wake up. Cloud Scheduler is very simple to set up, especially if you are familiar with cron in Linux.

For this article, I’ve written some Terraform code here that also triggers this job to scrape for books every day at 3:00AM EST.

Wrapping Up

Building a web scraping pipeline like this can be a rewarding experience. It bridges the potential gap between raw web data and meaningful insights. I believe I’ve found a sweet spot with the tools highlighted above, as they’ve met a variety of web scraping needs. Their modularity makes it easy to swap components in and out based on specific requirements. Google Sheets works well as an initial landing zone, leveraging a tool like BigQuery for advanced insights or machine learning in later stages makes this process even more exciting.

While I have used a lot of Google tools here, this can easily be transferred to other Cloud platforms, on-premise, or even in a small home lab. When I first started with data scraping, I used a single node Microk8s RaspberryPi instance that leveraged Kubernetes CronJobs to execute Scrapy. A bit overkill and this can easily be done with Linux cron, it shows that this really run anywhere and with very little compute.

I hope that by reading this, you’ve learned how easy it can be to build your own web scraping data pipeline. If you’re interested in learning more about the different variations of the pipelines I have, let me know!